When computers became widely used at the workplace in the 1970s, users worked at 'dumb' terminals, which were simply attachments to a mainframe. The 1980s, however, saw the victory of an idea which only a few visionaries had dared to entertain: they brought the computer to every desk - the personal computer, or PC.

The fact that PCs became omnipresent and revolutionized the computer industry within just a few years is not simply the result of technical progress. The presence of PCs at the workplace today is the result of the activities of people who, as vendors or users of hardware or software, envisaged implementing a computer that was what they wanted.

The emergence of the PC shows that new technologies, no matter how remarkable they may be, only result in really new applications when people adopt them for their own special purposes.

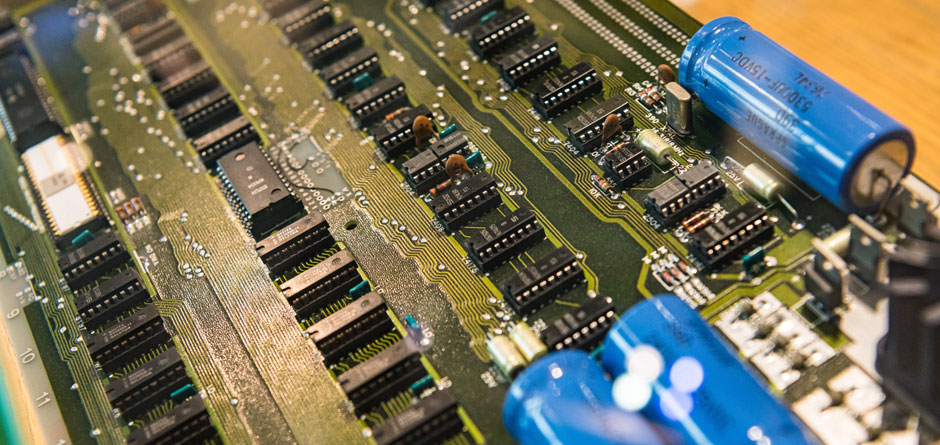

From today's point of view, Intel's first microprocessor had, in 1971, basically made everything available that was needed for a small universal computer.

Suggestions had been made for PC-like products at all large computer manufacturers but these were not welcomed in the early 1970s. Industrial magnates decided that there was simply no market for personal computers.

Long-haired nerds

At the end of the 1970s, it was long-haired freaks in sandals who were to teach the major computer companies that there was just such a market. In just a few years, the irreverent spirit of the flower children linked with enthusiasm for technology and entrepreneurship gave rise to countless small firms, many of which literally set up business in garages. An industry worth billions evolved.

Later, too, it proved that technical progress and market success did not always go hand in hand. Many a firm in the fast-moving PC sector had to learn the lesson that sudden changes in user needs could determine the success or failure of its business.

At first, nobody could imagine that anyone would want computers like the first PCs because nobody really knew what they were good for. Nevertheless, they were to become a tremendous success.

Icons, windows and mice

When IBM then finally brought out its first PC in 1981, people complained about its MS-DOS operating system, which was considered to be second choice. However, customers held Big Blue's reputation to be more important than the state of technology in the product, and made the IBM PC the standard for office applications. The operating system of the Apple Macintosh, however, was revolutionary in 1984. It brought icons, windows and mice to desktops but the Mac did not sell well until an application - desktop publishing - appeared for which the Mac was more suited than any other computer.

This boom was, of course, fostered by advances in semiconductor technology. Moore's Law illustrates the dynamism of this industry. He predicted that the power and complexity of computer chips would double, and their price halve, every 18 months.

This made it possible to run applications that required ever increasing computing power. Soon, PCs were processing still and moving pictures as well as sound. They became of interest to artists but, above all, gave rise to a huge market for entertainment products. In the computer industry, which originally developed for military customers, it is the producers of popular computer games that now set the tempo.

PCs were cheap, but there was still a market for more powerful desk-top computers made to meet the requirements placed by engineers and architects on computer-aided design rather than for office or home users. As in the case of PCs, these first workstations, as these computers were called in order to distinguish them from PCs, came from a newcomer to the scene - Sun Microsystems based in Silicon Valley.